degenerative scoliosis

Adult degenerative scoliosis is different from the type of scoliosis that occurs in teenagers. Adult degenerative scoliosis occurs after the spine has stopped growing and results from wear and tear of the spine. The condition most often affects the lumbar spine.

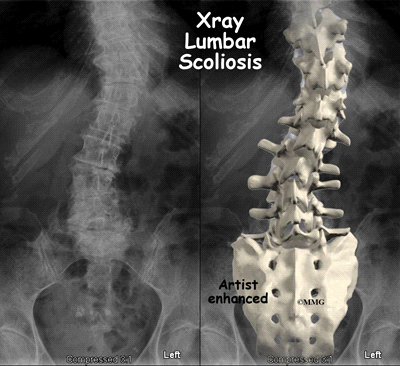

Adult degenerative scoliosis can be a result of scoliosis from childhood. The curvature may increase during adulthood and become painful.Most often the lumbar spine is affected. The vertebrae curve to one side and may rotate, which makes the waist, hips, or shoulders appear uneven.

The most common cause of adult degenerative scoliosis is from degeneration, known as wear and tear. It usually occurs after the age of 40. In older women, it is often related to osteoporosis. Osteoporosis is the loss of calcium in the supporting bone. This makes the vertebrae weak.

In adult degenerative scoliosis, the spine loses its structural stability and becomes unbalanced. This imbalance of the spine causes changes in the way the forces of the spine are directed. The larger the scoliotic curve becomes, the faster these changes cause degeneration of the spine. This creates a vicious cycle where increasing deformity causes more imbalance, that in turn causes more deformity. While this process occurs very slowly, it usually continues to slowly progress until something is done to restore the balance in the spine.

When there is an S curve when viewing the spine from the front, the condition is called scoliosis. The scoliotic deformity may also affect the normal S curve that the spine has when vised from the side. These curves are normal and required to maintain the proper balance of the spine. Many patients with scoliosis actually lose the normal curves of the spine.

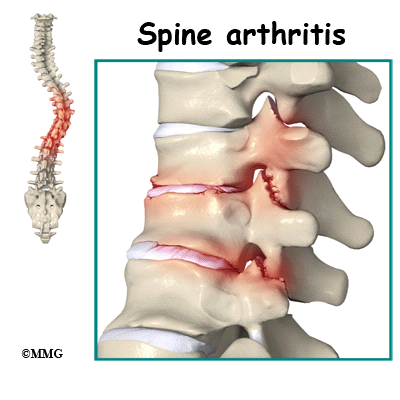

In adult degenerative scoliosis, there is gradual narrowing of the discs that cushion between the vertebrae. The cartilage and joint surfaces of the facet joints in the spine can wear out, causing arthritis. This can cause back pain.

.

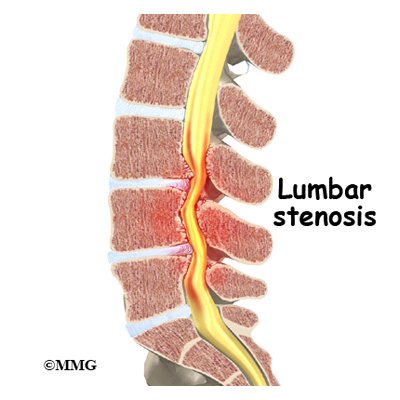

Stenosis is a term meaning narrowing. There are times when the canal for the spinal cord is narrowed. The openings for the nerve roots may also be narrowed. This will usually cause compression of the nerve structures. When the spinal cord or spinal nerves are compressed, pain, changes in feeling and/or motor function of the muscles can happen.

Degenerative scoliosis is more common the older we get. As our population ages, adult scoliosis will be even more common. It will be an increasing source of deformity, pain, and disability.

Most people who have scoliosis will notice the deformity it can cause. There is usually a hump (rib hump) in the back. One shoulder and/or side of the pelvis may be lower than the other. You may have noticed that you have shrunk in height. You may not be able to stand up straight. For many, there is no significant pain caused by the scoliosis. Other symptoms may include:

- Decreased range of motion or stiffness in the back

- Pain involving the spine

- Stiffness and pain after prolonged sitting or standing

- Pain when lifting and carrying

- Pain may travel to areas away from the spine itself. It may cause pain in the buttocks or legs

- Spasm of the nearby muscles

- Difficulty walking

- Difficulty breathing

Your doctor will ask you several questions about your pain, function, what makes your pain better and worse, when it started, bowel or bladder function, motor function, and whether you have had previous surgery.Your doctor will perform a physical examination that will include observation of your posture in standing position both sideways and from the front and back to assess for scoliosis. Mobility of your spine and hips, as well as walking ability will be evaluated.A neurological exam that includes testing reflexes with a small rubber hammer, and testing of sensation will likely be included.

Your doctor will want to start with x-rays to measure the degree of the scoliosis. X-rays provide pictures of the alignment of the vertebra. Using a device to measure angles held up to the x-ray image, the degree of curvature of the spine can be measured. X-rays can also give your doctor information about how much degeneration has occurred in the spine. They show the amount of space between the vertebrae.

If you are having pain into your leg(s), or difficulty with bowel or bladder function, your doctor will likely order a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. The MRI scan provides a better image of the soft tissues such as discs, nerves, and the spinal cord. The MRI machine uses magnetic waves rather than x-rays to show the soft tissues of the spine. The pictures show slices of the area imaged.

Most of the time treatment of adult degenerative scoliosis is conservative care, meaning non-surgical. Rarely is surgery necessary. Treatment decisions for adult degenerative scoliosis are based on how much pain you are experiencing, how much the condition is affecting your ability to function and whether or not you are having symptoms of nerve compression.

Whenever possible, doctors prefer treatment other than surgery. The first goal of nonsurgical treatment is to ease pain and other symptoms so the patient can resume and maintain normal activities as soon as possible.

Your doctor may prescribe treatment from a physical therapist. Much of the pain from adult degenerative scoliosis is the result of muscle spasm. This spasms occurs when the normal muscles must work harder than normal try to restore the balance to the spine. The muscles become fatigued and begin to spasm. This causes pain.

The physical therapist can help you with positions and exercises to ease these symptoms. The therapist can design an exercise program to improve flexibility of tight muscles, to strengthen the back and abdominal muscles, and to help you move safely and with less pain.

You may also be prescribed medication to help you gain better control of your symptoms so you can resume normal activity swiftly. There are many anti-inflammatories available.

Bracing may provide some help especially when the scoliosis is painful or unstable. Braces that are made to fit may be more comfortable and effective but they are more expensive than off-the-shelf braces or supports. There are also unloading braces to help relieve pressure on the discs, nerves and joints of the spine.

If symptoms continue to limit your ability to function normally, your doctor may suggest an injection into the spine to help with pain. Your doctor may recommend facet injections into the joints of the spine. A procedure called radiofrequency ablation may provide more lasting benefit. Epidural or transforaminal injections into the spine can also be helpful. A series of injections may be more helpful to provide temporary decrease in pain.

If you have osteoporosis, discuss with your doctor how you can optimize your treatment for this condition to slow the progression of osteoporosis. Adequately treating the osteoporosis can help reduce the progression of the scoliosis.

Surgery is usually considered when non-surgical treatments have not provided enough relief from pain – or when the nerves of the spine are being damaged. Surgery is more common when the curvature is continuing to increase and the imbalance of the spine is clearly getting worse. Surgery to correct adult degenerative scoliosis is both complex and difficult. Most surgeons would not suggest surgical intervention except as a last resort when all conservative measures have failed and the pain is intolerable.

The goal of surgery is to improve the balance of the spine and remove pressure on any of the nerves of the spine. Surgery to relieve pressure on the nerves is called a decompression. Surgery to reinforce the area that is unstable is called a fusion.

Physical therapy is important for strengthening muscles of the spine, abdomen, hip girdle, and legs. Stretching of certain muscles may also be recommended. Stretching or traction applied to the sides of the curve is sometimes used by physical therapists. Exercises must be done on a regular, ongoing basis. It may be possible to improve posture and motion.

Activity modification such as limited lifting or avoidance of prolonged sitting or standing may be helpful. Occasional use of a cane or walker to improve walking tolerance may be recommended.

Use of ice or heat may prove beneficial. Your doctor or physical therapist can provide you with guidelines.

Your physical therapist may advise you to participate in weight bearing exercises to help strengthen your bones and muscles. These may include activities such as walking, toning with the use of weights or other resistance.

Your surgeon may suggest a brace following surgery, to ensure that you do not bend too far and to support your spine.

You will be allowed to get in and out of bed and walk shortly after surgery. Lifting is usually limited during the initial recovery period. You will gradually be allowed to resume your usual activities after several weeks or months.

It may be recommended that you have physical and occupational therapy after your surgery to help you regain strength and independence with daily activity. They also will help you with activity modification.

Intervertebral disc herniation

A herniated disc (also called bulged, slipped or ruptured) is a fragment of the disc nucleus that is pushed out of the annulus, into the spinal canal through a tear or rupture in the annulus. The spinal canal has limited space, which is inadequate for the spinal nerve and the displaced herniated disc fragment. Due to this displacement, the disc presses on spinal nerves, often producing pain, which may be severe.

Herniated discs can occur in any part of the spine. Herniated discs are more common in the lower back (lumbar spine), but also occur in the neck (cervical spine).

Lumbar spine (lower back): Sciatica/Radiculopathy frequently results from a herniated disc in the lower back. Pressure on one or several nerves that contribute to the sciatic nerve can cause pain, burning, tingling and numbness that radiates from the buttock into the leg and sometimes into the foot.

Cervical spine (neck): Cervical radiculopathy is the symptoms of nerve compression in the neck, which may include dull or sharp pain in the neck or between the shoulder blades, pain that radiates down the arm to the hand or fingers or numbness or tingling in the shoulder or arm

Application of radiation to produce a film or picture of a part of the body can show the structure of the vertebrae and the outline of the joints.

A diagnostic test that produces 3D images of body structures using powerful magnets and computer technology; can show the spinal cord, nerve roots and surrounding areas as well as enlargement, degeneration and tumors.

These tests measure the electrical impulse along nerve roots, peripheral nerves and muscle tissue. This will indicate whether there is ongoing nerve damage, if the nerves are in a state of healing from a past injury or whether there is another site of nerve compression. This test is infrequently ordered.

The initial treatment for a herniated disc is usually conservative and nonsurgical. A doctor may advise the patient to maintain a low, painless activity level for a few days to several weeks. This helps the spinal nerve inflammation to decrease. Bedrest is not recommended.

A herniated disc is frequently treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication, if the pain is only mild to moderate. An epidural steroid injection may be performed utilizing a spinal needle under X-ray guidance to direct the medication to the exact level of the disc herniation.

The doctor may recommend physical therapy. Pain medication and muscle relaxants may also be beneficial in conjunction with physical therapy.

A doctor may recommend surgery if conservative treatment options, such as physical therapy and medications, do not reduce or end the pain altogether. Doctors discuss surgical options with patients to determine the proper procedure

A patient may be considered a candidate for spinal surgery if:

- Radicular pain limits normal activity or impairs quality of life

- Progressive neurological deficits develop, such as leg weakness and/or numbness

- Loss of normal bowel and bladder functions

- Difficulty standing or walking

- Medication and physical therapy are ineffective

Lumbar canal stenosis

According to the North American Spine Society (NASS), spinal stenosis describes a clinical syndrome of buttock or leg pain. These symptoms may occur with or without back pain. It is a condition in which the nerves in the spinal canal are closed in, or compressed. The spinal canal is the hollow tube formed by the bones of the spinal column. Anything that causes this bony tube to shrink can squeeze the nerves inside. As a result of many years of wear and tear on the parts of the spine, the tissues nearest the spinal canal sometimes press against the nerves. This helps explain why lumbar spinal stenosis (stenosis of the low back) is a common cause of back problems in adults over 55 years old.

In the lumbar spine, the spinal canal usually has more than enough room for the spinal nerves. The canal is normally 17 to 18 millimeters around, slightly smaller than a penny. Spinal stenosis develops when the canal shrinks to 12 millimeters or less. When the size drops below 10 millimeters, severe symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis occur.

There are many reasons why symptoms of spinal stenosis develop.

Congenital stenosis: Some people are born with (congenital) a spinal canal that is narrower than normal. They may not feel problems early in life. However, having a narrow spinal canal puts them at risk for stenosis. Even a minor back injury can cause pressure against the spinal cord. People born with a narrow spinal canal often have problems later in life, because the canal tends to become narrower due to the effects of aging.

Degeneration: Degeneration is the most common cause of spinal stenosis. Wear and tear on the spine from aging and from repeated stresses and strains can cause many problems in the lumbar spine. The intervertebral disc can begin to collapse, and the space between each vertebrae shrinks. Bone spurs may form that stick into the spinal canal and reduce the space available to the spinal nerves. The ligaments that hold the vertebrae together may thicken and also push into the spinal canal. All of these conditions cause the spinal canal to narrow.

Spinal instability: Spinal instability can cause spinal stenosis. Spinal instability means that the bones of the spine move more than they should. Instability in the lumbar spine can develop if the supporting ligaments have been stretched or torn from a severe back injury. People with diseases that loosen their connective tissues may also have spinal instability. Whatever the cause, extra movement in the bones of the spine can lead to spinal stenosis.

Disc herniation: Spinal stenosis can occur when an intervertebral disc in the low back herniates (ruptures). Normally, the shock-absorbing disc is able to handle the downward pressure of gravity and the strain from daily activities. However, if the pressure on the disc is too strong, such as landing from a fall in a sitting position, the nucleus inside the disc may rupture through the outer annulus and squeeze out of the disc. This is called a disc herniation. If an intervertebral disc herniates straight backward, it can press against the nerves in the spinal canal, causing symptoms of spinal stenosis.

Spinal stenosis usually develops slowly over a long period of time. This is because the main cause of spinal stenosis is spinal degeneration in later life. Symptoms rarely develop quickly when degeneration is the source of the problem. A severe injury or a herniated disc may cause symptoms to develop immediately.

Patients with stenosis don’t always feel back pain. Primarily, they have severe pain and weakness in their legs, usually in both legs at the same time. Some people say they feel that their legs are going to give out on them.

Symptoms mainly affect sensation in the lower limbs. Nerve pressure from stenosis can cause a feeling of pins and needles in the skin where the spinal nerves travel. Reflexes become slowed. Some patients report charley horses in their leg muscles. Others report strange sensations like water trickling down their legs.

Symptoms change with the position of the low back. Flexion (bending forward) widens the spinal canal and usually eases symptoms. That’s why people with stenosis tend to get relief when they sit down or curl up to sleep. Activities such as reaching up, standing, and walking require the spine to straighten or even extend (bend back slightly). This position of the low back makes the spinal canal smaller and often worsens symptoms.

Diagnosis begins with a complete history and physical examination. Your doctor will ask questions about your symptoms and how your problem is affecting your daily activities. This will include questions about your pain or if you have feelings of numbness or weakness in your legs.

Your doctor will also want to know whether your symptoms are worse when you’re up standing or walking and if they go away when you sit down. If your pain does not get worse when walking, then you probably don’t have stenosis. There may be some other cause of the painful symptoms.

The doctor does a physical examination to see which back movements cause pain or other symptoms. Your skin sensation, muscle strength, and reflexes are also tested.

X-rays can show if the problems are from changes in the bones of the spine. The images can show if degeneration has caused the space between the vertebrae to collapse. X-rays may also show any bone spurs sticking into the spinal canal.

The best way to see the effects and extent of lumbar spinal stenosis is with a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. The MRI machine uses magnetic waves rather than X-rays to show the soft tissues of the body. This test gives a clear picture of the spinal canal and whether the nerves inside are being squeezed. This machine creates pictures that look like slices of the area your doctor is interested in. The test does not require dye or a needle.

Unless your condition is causing significant problems or is rapidly getting worse, most doctors will begin with nonsurgical treatments. Up to one-half of all patients with mild-to-moderate lumbar spinal stenosis can manage their symptoms with conservative (nonsurgical) care. Neurologic decline and paralysis in this group is rare.

At first, doctors may prescribe ways to immobilize the spine. Keeping the back still for a short time can calm inflammation and pain. This might include one to two days of bed rest. Patients may find that curling up to sleep or lying back with their knees bent and supported gives the greatest relief. These positions flex the spine forward, which widens the spinal canal and can ease symptoms.

A lumbar support belt or corset may be prescribed, though their benefits are controversial. Lumbosacral corsets do not appear to offer any long-term benefits. The support provides symptom relief only while you are wearing it. The support can limit pressure in the discs and prevent extra movement in the spine. But it can also cause the back and abdominal muscles to weaken. Some doctors have their patients wear a rigid brace that holds the spine in a slightly flexed position, widening the spinal canal. Health care providers normally only have patients wear a corset for one to two weeks.

Doctors sometimes prescribe medication for patients with spinal stenosis. These medications can cause side effects in the kidneys and gastrointestinal tract. Also, because most stenosis patients are elderly, doctors closely monitor patients who are using these medications to avoid complications.

Muscle relaxants are occasionally used to calm muscles in spasm.

Some patients are given an epidural steroid injection (ESI). The spinal cord is covered by a material called dura. The space between the dura and the spinal column is called the epidural space. It is thought that injecting steroid medication into this space fights inflammation around the nerves, the discs, and the facet joints. This can reduce swelling and give the nerves more room inside the spinal canal.

Your therapist may also suggest strengthening and aerobic exercises. Strengthening exercises focus on improving the strength and control of the back and abdominal muscles.

If the symptoms you feel are mild and there is no danger they’ll get worse, surgery is not usually recommended.

But for anyone with severe symptoms of lumbar spinal stenosis, surgery may be needed. When there are signs that pressure is building on the spinal nerves, decompressive surgery may be required, sometimes right away. Decompression means that bone and/or soft tissue are removed from around the spinal nerves to take the pressure off. The signs doctors watch for when reaching this decision include weakening in the leg muscles, pain that won’t ease up, and problems with the bowels or bladder.

Pressure on the spinal nerves can cause a loss of control in the bowels or bladder. This is an emergency. If the pressure isn’t relieved, it can lead to permanent paralysis of the bowels and bladder. Surgery is recommended to remove pressure from the nerves.

Even if you don’t need surgery, your doctor may recommend that you work with a physical or occupational therapist. Patients are normally seen a few times each week for one to two months. In severe cases, patients may need a few additional weeks of care.

Your therapist creates a program to help you regain back movement, strength, endurance, and function. Treatments for lumbar spinal stenosis often include lumbar traction. Therapists also guide patients in a program of exercise designed to widen the spinal canal and take pressure off the spinal nerves.

It is important to improve the strength and coordination in the abdominal and low back muscles. Your therapist can also evaluate your workstation or the way you use your body when you do your activities and suggest changes to avoid further problems.

After surgery, surgeons may have their patients work with a physical or occupational therapist.

During therapy after surgery, the therapist may use treatments such as heat or ice, electrical stimulation, and massage to help calm pain and muscle spasm. Then patients begin learning how to move safely with the least strain on their healing back.

As the rehabilitation program evolves, patients do more challenging exercises. The goal is to safely advance strength and function. As the therapy sessions come to an end, therapists help patients get back to the activities they enjoy. Ideally, patients are able to resume normal activities. Patients may need guidance on which activities are safe or how to change the way they go about certain activities

Spondylolisthesis

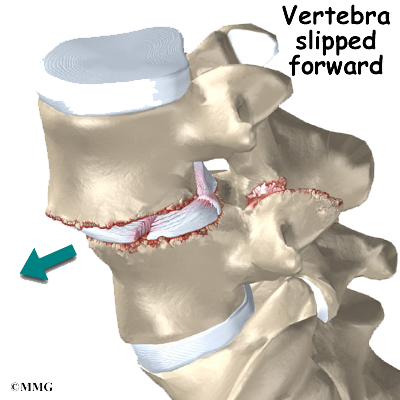

Normally, the bones of the spine (the vertebrae) stand neatly stacked on top of one another. Ligaments and joints support the spine. Spondylolisthesis alters the alignment of the spine. In this condition, one of the spine bones slips forward over the one below it. As the bone slips forward, the nearby tissues and nerves may become irritated and painful.

Spondylolisthesis may very rarely be congenital, which means it is present at birth. It can also occur in childhood as a result of injury. In older adults, degeneration of ponthe disc and facet (spinal) joints can lead to spondylolisthesis.

Spondylolisthesis from degeneration usually affects people over 50 years old. This condition occurs in African Americans more often than in whites. Women are affected more often than men. The effect of the female hormone estrogen on ligaments and joints is to cause laxity or looseness. The higher levels of estrogen in women may account for the greater incidence of spondylolisthesis. Degenerative spondylolisthesis mainly involves slippage of L4 over L5.

In younger patients (under 20 years old), spondylolisthesis usually involves slippage of the fifth lumbar vertebra over the top of the sacrum. There are several reasons for this. First, the connection of L5 and the sacrum forms an angle that is tilted slightly forward, mainly because the top of the sacrum slopes forward. Second, the slight inward curve of the lumbar spine creates an additional forward tilt where L5 meets the sacrum. Finally, gravity attempts to pull L5 in a forward direction.

Facet joints are small joints that connect the back of the spine together. Normally, the facet joints connecting L5 to the sacrum create a solid buttress to prevent L5 from slipping over the top of the sacrum. However, when problems exist in the disc, facet joints, or bony ring of L5, the buttress becomes ineffective. As a result, the L5 vertebra can slip forward over the top of the sacrum.

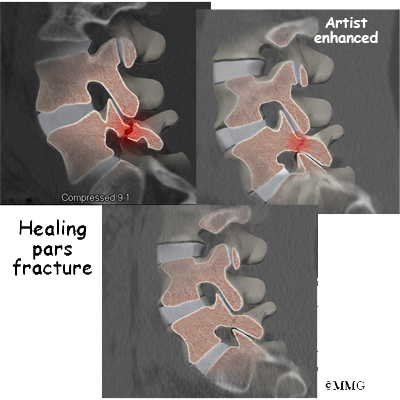

A condition called spondylolysis can lead to the slippage that happens with spondylolisthesis. Spondylolysis is a defect in the bony ring of the spinal column. It affects the pars interarticularis, mentioned earlier. This defect is most commonly thought to be a stress fracture that happens from repeated strains on the bony ring. Participants in gymnastics and football commonly suffer these strains. Spondylolysis can lead to the spine slippage when a fracture occurs on both sides of the bony ring. This slippage is called spondylolisthesis. The back section of the bony ring separates from the main vertebral body, so the injured vertebra is no longer connected by bone to the one below it. In this situation, the facet joints can’t provide their normal support. The vertebra on top is then free to slip forward over the one below.

Degenerative changes in the spine (those from wear and tear) can also lead to spondylolisthesis. The spine ages and wears over time, much like hair turns gray. These changes affect the structures that normally support healthy spine alignment. Degeneration in the disc and facet joints of a spinal segment causes the vertebrae to move more than they should. The segment becomes loose, and the added movement takes an additional toll on the structures of the spine. The disc weakens, pressing the facet joints together. Eventually, the support from the facet joints becomes ineffective, and the top vertebra slides forward.

An ache in the low back and buttock areas is the most common complaint in patients with spondylolisthesis. Pain is usually worse when standing, walking, or bending backward and may be eased by resting or bending the spine forward. Leaning on a counter top, piece of furniture, or shopping cart are common ways to alleviate (reduce) the symptoms.

Spasm is also common in the low back muscles. The hamstring muscles on the back of the thighs may become tight.

The pain can be from mechanical causes. Mechanical pain is caused by wear and tear on the parts of the spine. When the vertebra slips forward, it puts a painful strain on the disc and facet joints.

Slippage can also cause nerve compression. Nerve compression is a result of pressure on a nerve. As the spine slips forward, the nerves may be squeezed where they exit the spine. This condition also reduces space in the spinal canal where the vertebra has slipped. This can put extra pressure on the nerve tissues inside the canal. Nerve compression can cause symptoms where the nerve travels and may include numbness, tingling, slowed reflexes, and muscle weakness in the legs.

Nerve pressure on the cauda equina (mentioned earlier), the bundle of nerve roots within the lumbar spinal canal, can affect the nerves that go to the bladder and rectum. When this happens, bowel and/or bladder function can be affected. The pressure may cause low back pain, pain running down the back of both legs, and numbness or tingling between the legs in the area you would contact if you were seated on a saddle.

Diagnosis begins with a complete history and physical exam. Your doctor will ask questions about your symptoms and how your problem is affecting your daily activities. Your doctor will also want to know what positions or activities make your symptoms worse or better.

Next the doctor examines you by checking your posture and the amount of movement in your low back. Your doctor checks to see which back movements cause pain or other symptoms. Your skin sensation, muscle strength, and reflexes are also tested.

Doctors will usually order X-rays of the low back. The X-rays are taken with your spine in various positions. They can be used to see which vertebra is slipping and how far it has slipped.

Your doctor may also order a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan. The MRI machine uses magnetic waves rather than X-rays to show the soft tissues of the body. It can help in the diagnosis of spondylolisthesis. It can also provide information about the health of nerves and other soft tissues.

Studies have not been done yet to determine the best treatment for this condition. Conservative care is preferred, especially when the vertebra hasn’t slipped very far. Most patients with symptoms from degenerative spondylolisthesis do not need surgery and respond well to nonoperative care. Medications may be prescribed to help ease pain and muscle spasm. In some cases, the patient’s condition is simply monitored to see if symptoms improve.

Your doctor may ask that you rest your back by limiting your activities. This is to help decrease inflammation and calm muscle spasm. You may need to take time away from sports or other strenuous activities to give your back a chance to heal.

If your doctor diagnoses an acute pars fracture that has the potential to heal, it may be recommended that you wear a rigid back brace for two to three months. This usually occurs in children and teenagers who begin having back pain and see their doctor early on.

Some patients who continue to have symptoms are given an epidural steroid injection (ESI). Steroids are powerful anti-inflammatories, meaning they reduce pain and swelling. In an ESI, medication is injected into the space around the lumbar nerve roots. This area is called the epidural space. Some doctors inject only a steroid. Most doctors, however, combine a steroid with a long-lasting numbing medication. Generally, an ESI is given only when other treatments aren’t working. But ESIs are not always successful in relieving pain. If they do work, they may only provide temporary relief.

Patients often work with a physical therapist. After evaluating your condition, your therapist can assign positions and exercises to ease your symptoms. Your therapist can design an exercise program to improve flexibility in your low back and hamstrings and to strengthen your back and abdominal muscles.

Surgery is used when the slip is severe and when symptoms are not relieved with nonsurgical treatments. Symptoms that cause an abnormal walking pattern, changes in bowel or bladder function, or steady worsening in nerve function require surgery. Deterioration of symptoms is common in patients with a history of significant neurologic symptoms who don’t have surgery to correct the problem.

If a reasonable trial of conservative care (three months or more) does not improve things and/or your quality of life is significantly reduced, then surgery may be the next best solution. The main types of surgery for spondylolisthesis include

- laminectomy (decompression)

- posterior fusion with or without instrumentation

- posterior lumbar interbody fusion

Back pain associated with spondylolisthesis will gradually improve in up to one-third of all patients. Slippage of one vertebra over the other does not increase in this group. Worsening of symptoms is not expected in patients who don’t have neurologic symptoms at the time of diagnosis.

Nonsurgical treatment for spondylolisthesis commonly involves physical therapy. Your doctor may recommend that you work with a physical therapist a few times each week for four to six weeks. In some cases, patients may need a few additional weeks of care.

The first goal of treatment is to control symptoms. Your therapist works with you to find positions and movements that ease pain. Treatments of heat, cold, ultrasound, and electrical stimulation may be used to calm pain and muscle spasm. Patients are shown how to stretch tight muscles, especially the hamstring muscles on the back of the thigh.

As patients recover, they gradually advance in a series of strengthening exercises for the abdominal and low back muscles. Working these core muscles helps patients move easier and lessens the chances of future pain and problems.

Rehabilitation after surgery is more complex. Patients who have surgery for spondylolisthesis usually stay in the hospital for a few days afterward.

Some surgeons require patients to wear a rigid brace or cast for up to four months after fusion surgery for spondylolisthesis.